If a child is in immediate danger, call 911.

The Mandated Reporter is required to report even if their knowledge is incomplete. The role of the Mandated Reporter is to assess for reasonable cause to suspect abuse. The Mandated Reporter identifies reasonable cause and leaves the investigation to specially trained workers in the designated child welfare agency (PA General Assembly, n.d.).

The Mandated Reporter does not (PA General Assembly, n.d.):

- Investigate

- Interrogate

- Determine the perpetrator and their relationship to the child

When talking with children to establish reasonable cause, find a private place, and remain calm. Be honest, open, and upfront with the child. Be supportive. Listen to the child and stress that it's not the child's fault. Do not overreact, make judgments, make promises, nor interrogate or investigate.

There is no legal requirement to inform the parent or other persons legally responsible for the child’s care that you are making a report to ChildLine (PA General Assembly, n.d.). In fact, informing the parents of the report may place the child at risk of harm. Do not assume that the parent will support the child.

In the case of suspected sexual abuse, avoid talking in detail with the child about the incident. There are special guidelines that apply to the case of suspected sexual abuse. Usually, the designated child welfare agency and law enforcement work together to interview the child at the same time using specially trained professionals (PA General Assembly, n.d.).

Reasonable cause to suspect may be a determination you make based on your training/experience and all known circumstances – to include “who”, “what”, “when”, and “how”, observations (e.g., indicators of abuse or "red flags", behavior/demeanor of the child(ren), behavior/demeanor of the adult(s), etc.), as well as familiarity with the individuals (e.g., family situation and relevant history or similar prior incidents, etc.) Some indicators may be more apparent than others depending on the type of abuse and/or depending on the child's health, developmental level, and well-being. For example, some indicators may be visible on the child's body while other indicators may be present in the child's behaviors (DHS, 2024b). If there is reasonable cause to suspect the child is being abused or maltreated, you must call ChildLine immediately (DHS, 2024b).

The individuals listed above are the Mandated Reporters for the state of Pennsylvania (DHS, 2024b). A Mandated Reporter shall immediately make an oral/verbal report of suspected child abuse to DHS via the Statewide toll-free telephone number under section 6332 (relating to establishment of Statewide toll-free telephone number) (1-800-932-0313) or a written report using electronic technologies under section 6305 (relating to electronic reporting) (via the self-service line here.

Mandated Reporters are required to make a report of suspected child abuse in accordance with section 6313 (relating to reporting procedure) if the Mandated Reporter has reasonable cause to suspect that a child is a victim of child abuse under any of the following circumstances (DHS, 2024b; PA General Assembly, n.d.):

- They come into contact with the child in the course of employment, occupation, and practice of a profession or through a regularly scheduled program, activity, or service.

- They are directly responsible for the care, supervision, guidance, or training of the child, or are affiliated with an agency, institution, organization, school, regularly established church or religious organization or other entity that is directly responsible for the care, supervision, guidance, or training of the child.

- A person makes a specific disclosure to the Mandated Reporter that an identifiable child is the victim of child abuse.

- An individual 14 years of age or older makes a specific disclosure to the Mandated Reporter that the individual has committed child abuse.

Nothing in section 6311 of the PA CPSL (relating to persons required to report suspected child abuse) shall require a child to come before the Mandated Reporter in order to make a report of suspected child abuse (DHS, 2024b).

Nothing in section 6311 of the PA CPSL (relating to persons required to report suspected child abuse) shall require the Mandated Reporter to identify the person responsible for the child abuse in order to make a report of suspected child abuse.

- Crimes committed against the child should be reported directly to law enforcement. If you are uncertain if the incidence is criminal, you can contact the designated child welfare agency anyway. If the child is in imminent danger, contact law enforcement immediately.

Whenever a person is required to report under subsection (b) (relating to basis to report) in the capacity as a member of the staff of a medical or other public or private institution, school, facility, or agency, that person shall report immediately in accordance with section 6313 (relating to reporting procedure) and shall immediately thereafter notify the person in charge of the institution, school, facility, or agency or the designated agent of the person in charge. Upon notification, the person in charge or the designated agent, if any, shall facilitate the cooperation of the institution, school, facility, or agency with the investigation of the report. Any intimidation, retaliation, or obstruction in the investigation of the report is subject to the provisions of 18 Pa.C.S. § 4958 (relating to intimidation, retaliation, or obstruction in child abuse cases).

The PA CPSL does not require more than one report from any such institution, school, facility, or agency, but the report should include the names and contact information of everyone who has knowledge of the situation (DHS, 2024b).

Reports of child abuse may be reported to ChildLine electronically if the situation does not require an emergency response. Mandated Reporters can report electronically here.

Establishment of Statewide toll-free telephone number (23 Pa.C.S. § 6332): The Statewide toll-free telephone number is available for all persons, whether mandated by law or not, to use to report cases of suspected child abuse or children allegedly in need of general protective services. You should call the Child Abuse Hotline, ChildLine at 1-800-932-0313 in the following situations:

- You do not know the county where the incident occurred

- The suspected abuse and/or neglect you are reporting occurred outside the state of Pennsylvania

- You are unsure if the child is at imminent risk of harm

- You have more than eight alleged perpetrators and/or the child has a list of extensive injuries

- You are unable to provide a Pennsylvania address for any person on the report

This toll-free hotline number is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

A Mandated Reporter making an oral/verbal report of suspected child abuse to the DHS via the Statewide toll-free telephone number under section 6332 (relating to establishment of Statewide toll-free telephone number) shall also make a written report (CY-47), which may be submitted electronically, within 48 hours to DHS or county agency assigned to the case in a manner and format prescribed by DHS.

This form can be obtained here at the top of the page. A direct download link is available here.

You can also obtain a copy from the county Children and Youth Services Agency.

The failure of the Mandated Reporter to file the written report (CY-47) shall not relieve the county agency from any duty under the PA CPSL, and the county agency shall proceed as though the Mandated Reporter complied.

If a report is made electronically, no form CY-47 is required to be completed.

Be prepared to articulate your concerns in a clear and concise manner when you call ChildLine. The following is a list of information that the Mandated Reporter is asked to provide in the written report if it is known (DHS, 2024b):

- The names and addresses of the child, the child's parents, and any other person responsible for the child's welfare

- Where the suspected abuse occurred

- The age and sex of each subject of the report

- The nature and extent of the suspected child abuse, including any evidence of prior abuse to the child or any sibling of the child

- The name and relationship of each individual responsible for causing the suspected abuse and any evidence of prior abuse by each individual

- Family composition

- The source of the report

- The name, telephone number, and e-mail address of the person making the report

- The actions taken by the person making the report, including those actions:

- Relating to photographs, medical tests, and X-rays of child subject to report (taken under section 6314)

- Relating to taking child into protective care (section 6315)

- Relating to admission to private and public hospitals (section 6316)

- Relating to mandated reporting and postmortem investigation of deaths (section 6317)

- Any other information required by Federal law or regulation

- Any other information that the Department of Human Services requires by regulation

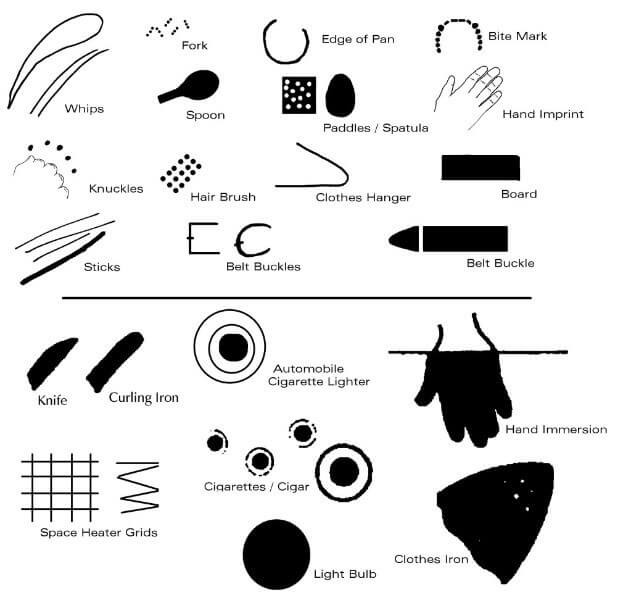

It is important to note here that the specific type of abuse is not required to be identified when making a report of suspected child abuse (DHS, 2024b). Permissible under Pennsylvania law, an individual who suspects possible child abuse may request photograph, a radiologic examination, and/or other medical testing of the child, depending on what is clinically indicated (Pennsylvania Code, 2024b). In the event that any of this takes place, it should accompany the report. All of the aforementioned images or medical summaries should be submitted with the written report or sent within 48 hours after the report is made electronically (Pennsylvania Code, 2024b).

Regarding confidentiality of reports (23 Pa.C.S. § 6339), except as otherwise provided in subchapter C of the PA CPSL (relating to powers and duties of department) or by the Pennsylvania Rules of Juvenile Court Procedure, reports made pursuant to the PA CPSL, including, but not limited to, report summaries of child abuse and reports made pursuant to section 6313 (relating to reporting procedure) as well as any other information obtained, reports written, or photographs or X-rays taken concerning alleged instances of child abuse in the possession of DHS or a county agency shall be confidential (DHS, 2024b).

The law requires that Mandated Reporters identify themselves and where they can be reached (DHS, 2024b). This information is helpful if the caseworker needs additional information. However, the identity of the person making the report is kept confidential, apart from being released to law enforcement officials or the district attorney's office (DHS, 2024b).

Release of Information in Confidential Reports (23 Pa.C.S. § 6340): Except for reports under section 6340(a)(9) and (10) of the PA CPSL and in response to a law enforcement official investigating allegations of false reports under 18 Pa.C.S. § 4906.1 (relating to false reports of child abuse), the release of data by DHS, county, institution, school, facility, or agency or designated agent of the person in charge that would identify the person who made a report of suspected child abuse or who cooperated in a subsequent investigation is prohibited. Law enforcement officials shall treat all reporting sources as confidential informants.

A Mandated Reporter who makes a report of suspected child abuse or who makes a report of a crime against a child to law enforcement officials shall not be in violation of the act of July 9, 1976 (P.L.817, No.143), known as the Mental Health Procedures Act, by releasing information necessary to complete the report (DHS, 2024b).

Mandated Reporting and Postmortem Investigation of Deaths (PA General Assembly, n.d.; DHS, 2024c): A person or official required to report cases of suspected child abuse, including employees of a county agency, who has reasonable cause to suspect that a child died as a result of child abuse shall report that suspicion to the appropriate coroner or medical examiner. The coroner or medical examiner shall accept the report for investigation and shall report his findings to the police, the district attorney, the appropriate county agency, and, if the report is made by a hospital, the hospital (DHS, 2024c).

If your agency or organization is an institution, facility, or agency which cares for children and is subject to supervision by PA DHS under Article IX of the Human Services (formerly Public Welfare) Code, make sure to look into your employer’s internal policies related to reporting suspected child abuse.

_800px.jpg)