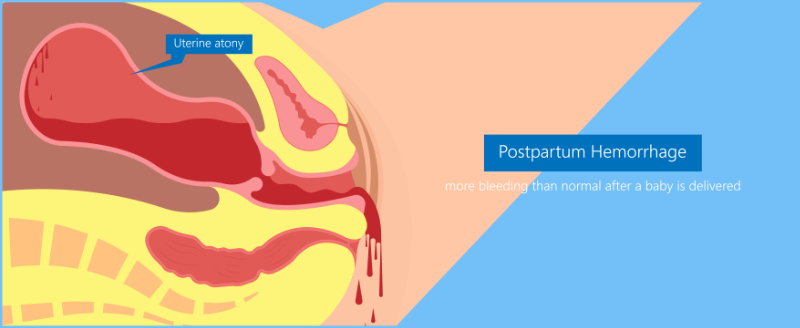

Postpartum hemorrhage risk assessments should be performed upon (CMQCC, 2022):

- Admission

- Pre-birth (at start of second stage of labor)

- Post-birth (transfer to postpartum)

- With any change in the patient’s condition

The Association for Women's Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nursing (AWHONN) created one version of a postpartum hemorrhage risk assessment that can be used to assess women for their risk of postpartum hemorrhage, as did the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC).

This tool is comprehensive because it looks at admission, pre-birth, and post-birth factors, all of which can affect a woman's risk of hemorrhage. The tool even gives suggestions for interventions based on the woman's risk. For example, a woman who is low-risk only needs a "type and hold" order from the blood bank, but a woman who is medium-risk should have a "type and screen" from the blood bank, and certain personnel should be notified of the risk (provider, charge RN, anesthesia, blood bank). A high-risk woman should have a "type and cross," notify personnel and possibly deliver at a tertiary care center (Colalillo et al., 2021).

To view this tool from AWHONN, please visit here. Then, click on the very first link at the top of the page with the title, “AWHONN’s Postpartum Risk Assessment Tool”.

The CMQCC also has a postpartum hemorrhage risk assessment similar to the AWHONN tool. To view the comprehensive tool from the CMQCC, please visit here. You will be asked to download a PDF version of the OB hemorrhage toolkit “Appendix K”, which contains the postpartum hemorrhage risk assessment as discussed above (CMQCC, 2022).

With any risk assessment, it is important to remember that admission risks will remain, but labor and delivery can impose new risks to the woman. Although postpartum hemorrhage can occur without any risks, a woman who is a moderate or high-risk patient should alert the nurse and providers to be prepared for the possibility of a postpartum hemorrhage at delivery (Colalillo et al., 2021).

Special consideration must be given to women who choose not to accept blood products, such as a woman who is a Jehovah's Witness. Women who are Jehovah’s Witnesses should be identified and counseled prenatally. The woman should be given information and a checklist to fill out, stating which products she wishes to receive or not receive. The woman should have a designated healthcare proxy. Some women will accept certain products, such as her blood, from a cell salvage system. It is important to have a care plan for this woman and have the information available at the hospital. It is also important that these women have their hematocrit measured regularly near the end of pregnancy so the woman can take iron, including intravenous iron as needed to optimize their hematocrit (CMQCC, 2022). These patients are at high-risk and have special needs before delivering their babies (CMQCC, 2022).