Patient Profile:

Kami is a 51-year-old nurse and military veteran who completed two tours in the Middle East. During her deployments, she began smoking as a coping mechanism to manage chronic stress and the constant threat of explosive devices. Though she considers herself physically fit and does not have diabetes, she has continued smoking since returning from duty.

Presenting Complaint:

For the past two weeks, Kami has experienced nighttime episodes of chest discomfort described as a crushing sensation radiating to her left arm. The most recent episode lasted approximately 30 minutes and extended to her shoulder and jaw. In response, she smoked a cigarette to alleviate her anxiety. She reports that the chest pain never occurred during menstruation, though she has not yet undergone menopause. Kami has no known allergies, is not pregnant, and her medical history is otherwise unremarkable.

Family History:

- Father: Deceased at age 71 due to myocardial infarction; had diabetes.

- Mother: Survived a stroke at age 70; currently diabetic but has no known history of CAD.

Initial Evaluation:

Upon presentation to the emergency department, Kami's vital signs were within normal limits:

- Oxygen saturation: 98%

- Heart rate: 82 beats per minute (bpm)

- Blood pressure: 128/70 millimeters of mercury (mmHg)

A comprehensive workup was initiated, including:

- ECG: Normal

- Chest X-ray: Normal

- Cardiac enzymes and lab work: Within normal limits

- Additional testing scheduled: Glucose tolerance test and cardiac stress test

Initial Clinical Impression and Management:

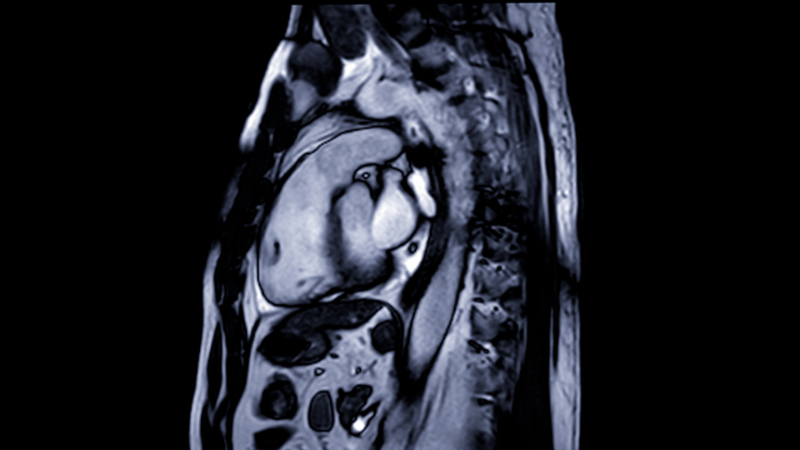

Despite unremarkable initial findings, Kami's symptoms and clinical history prompted her physician to suspect Prinzmetal angina (variant angina), a condition involving transient coronary artery vasospasms often occurring at rest and frequently during the night or early morning.

Initial Treatment Plan:

Sublingual Nitroglycerin: For immediate relief during acute vasospastic episodes.

Long-acting nitrate and calcium channel blocker: To improve coronary blood flow and prevent recurrence. Medication adjustments may be necessary based on therapeutic response.

Lifestyle Modification: Kami was strongly advised to quit smoking. A smoking cessation class was recommended, though pharmacologic support for cessation was deferred at this time.

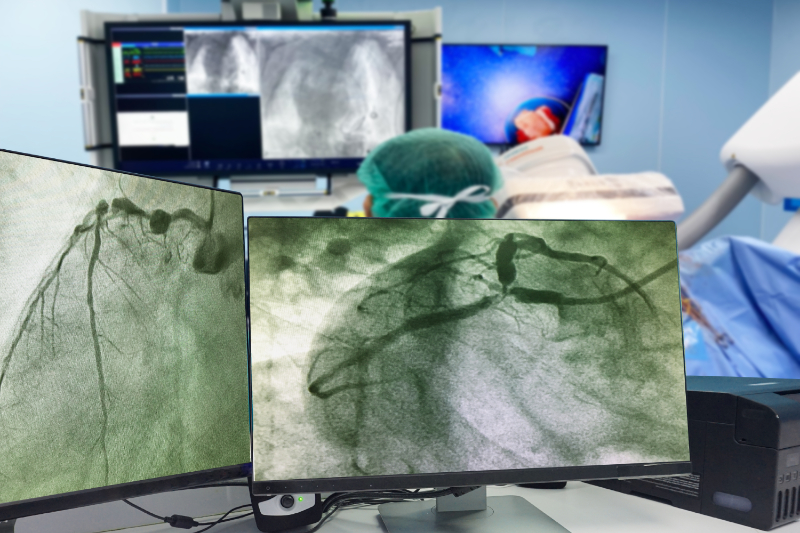

Contingency Plan: If Kami fails to respond to first-line therapy, her physician may introduce alpha-adrenergic blockers to lower blood pressure and counteract the vasoconstrictive effects of stress hormones. Should pharmacologic measures prove inadequate or if coronary obstruction develops, coronary angioplasty or other interventional procedures may be considered.

Prognosis and Follow-Up:

Kami was counseled that Prinzmetal angina is a chronic yet manageable condition. Symptoms often follow a cyclical pattern, and many patients see improvement with medical therapy over time. If well-controlled, medication tapering may be considered after 6–12 months. Regular follow-up and adherence to lifestyle modifications, especially smoking cessation, will be critical in preventing progression and maintaining cardiac health.