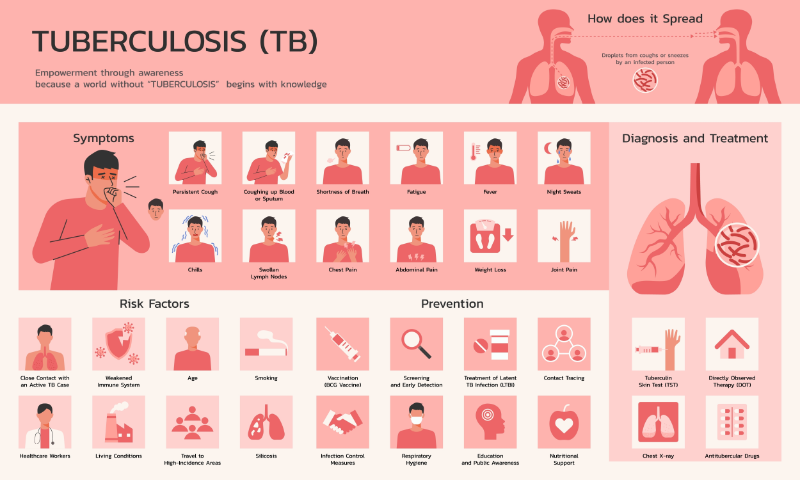

Tuberculosis is caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The main organs that are damaged by TB are the lungs (Nardell, 2023). TB bacteria are spread when someone inhales infected droplets(Nardell, 2023). The droplets are spread when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks (Nardell, 2023). Some of the infected droplets can remain in the air for several hours. Tuberculosis can also be spread by medical procedures that can create infected droplets. These are procedures like bronchoscopy, intubation, obtaining a saliva sample, and nebulizer treatments (Zachary, 2024).

Tuberculosis is not spread by casual contact, such as shaking hands, sharing food or beverages, kissing, or touching an infected person’s clothes or bed linens (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2025). The TB bacteria can be transmitted through the skin or other routes, but this is not uncommon.

How contagious untreated, active TB is can be variable. It depends on many things:

Table 1. Risk Factors for TB Transmission (Nardell, 2023; Traiman, 2024)

Risk Factors for TB Transmission- Close contact with an untreated, infected person

- Decreased immune system, e.g., HIV infection

- Crowded living situation

- Frequent contact with an untreated, infected person

- Contact with an untreated, infected person for a long time

- Poor ventilation

- The specific strain of bacteria

|

Close contact with someone who has untreated active TB, especially in a crowded space with bad ventilation, is a high-risk factor for TB transmission and infection (Traiman, 2024).

Tuberculosis can be spread from an infected mother during pregnancy and delivery (Friedman & Tanoue, 2024; Tesini, 2022). No cases of the spread of TB from breastfeeding have been reported (Loveday et al., 2020). Women who have active TB who are being treated with antitubercular drugs can breastfeed (CDC, 2020).

Dormant (latent) tuberculosis is not contagious (CDC, 2025). The next section discusses latent TB.

The risk of an infected person spreading TB decreases when they begin taking antitubercular drugs (Nardell, 2023). When the TB bacteria in their spit is not infectious, they cough much less (Nardell, 2023). Infection control is discussed later in the course. There is evidence that if the patient responds to several weeks of drug treatment, TB will not be transmitted, even with close contact (Nardell, 2023).