| “In the 1960s, unions helped mobilize hundreds of thousands of workers and their unions to push for federal legislation that ultimately resulted in the passage of the Mine Safety and Health Act of 1969 and the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970” (Rosner & Markowicz, 2020). |

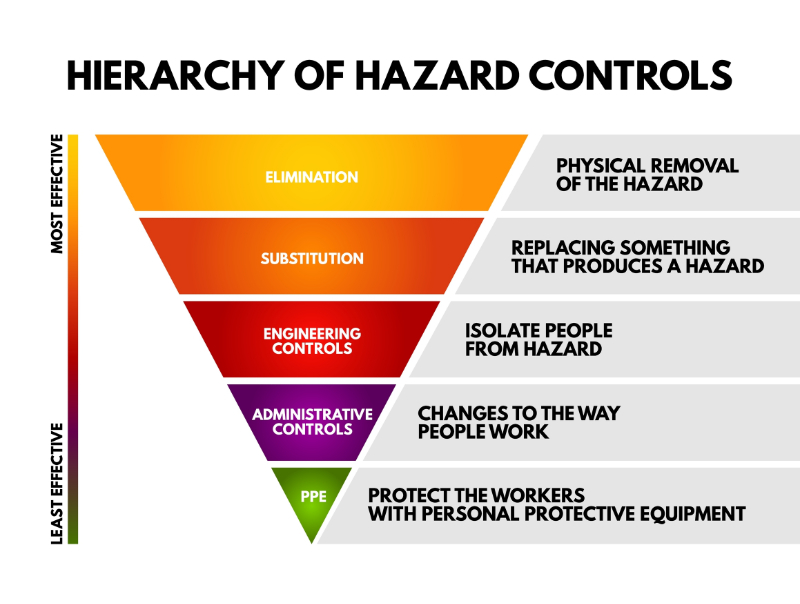

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is a federal and state government program created in 1970 to protect workers from known work hazards in mostly manufacturing industries(Rosner & Markowitz, 2020). OSHA inspects workplaces for various programmed and unprogrammed themes, such as multidrug-resistant organism safety, exposure to hazardous chemicals, and other things like waste gases, lasers, and radiation. According to OSHA, every worker has the right to work in a safe environment. As a governmental agency, OSHA can fine companies for workplace safety rule infractions. Also, as a government agency, the strictness of policy enforcement is contingent on the changing political ideology in the country's administration and agency. OSHA publishes compliance information, safety training materials, and extensive occupational safety articles on the website here. OSHA regulates workplace hazard communication signs, caution, safety, and biohazard signs. The OSHA standard includes sign colors, shapes, wording rules, accuracy, and even the tone of the message on the signs (positive rather than negative)(Nemmers, 2022). Why are HCWs getting hurt despite the hazardous communications all around them in every room, department, and corridor?

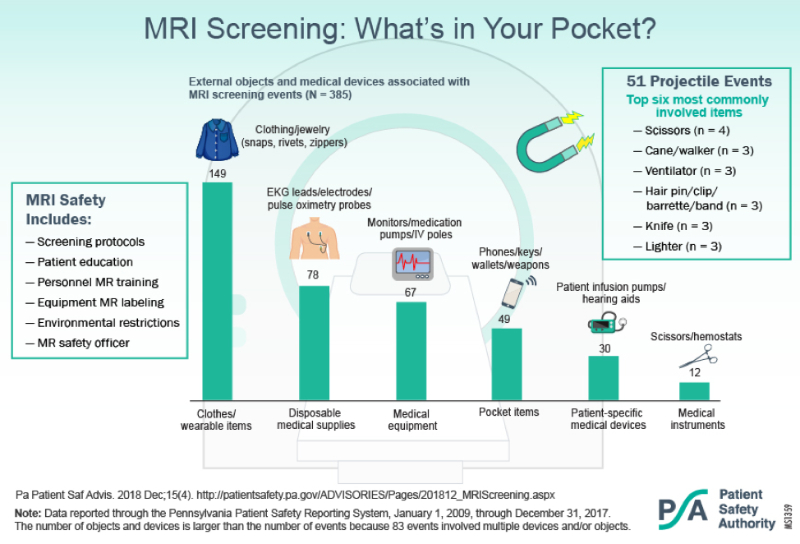

The problem with hazard communications is that multiple signs create a condition similar to alarm fatigue. Dr. Green (2024) said that workers fatigued by warning signs began performing their jobs riskier due to the warning insensitivity. When healthcare workers see the same WARNING signs in the same places day after day, they become habituated to them and become as good as invisible. A fascinating study by Kim et al. (2023) reported that virtual reality (VR) accident training helped to decrease this sign fatigue, providing safer outcomes. Students who were tested for warning sign fatigue by Vance et al. (2017) forgot which signs they had been seeing regularly. They report that polymorphic signage, signs that create a small visual variation, reduce sign fatigue, and sustained novelty over time. They also found that if the signs were moved up or down or closer to the actual risk, they were noticed more. The study by Vance et al. (2023) also enumerated that although the students spoke the language of the signs, they did not always understand the hazard’s significance, such as why a particular area was a no-smoking area. Pictograms showing an explosion combined with the no smoking sign were more effective with fewer words. Signage may be adjusted in some types of signs, such as color, size, and orientation, according to the OSHA Standards, if they are not mandated (Nemmers, 2022). All the hazard communication in the world will not help a person stay safe unless they are motivated to obey them and avoid the warned action. Dr. Green (2024) makes an interesting point about whether or not the danger or warning sign will be obeyed depending on each person’s psychological approach. His point is that many calculations are going on when someone decides to deliberately ignore a warning sign, based on that person’s thinking process goals, the costs to attain them, their perception of the danger, and “personal and social and cultural decision-making factors” (Green, 2024). To follow this through, think of the person who sees a 55-mph sign while driving. Whether to obey it will be subject to automatic thoughts and calculations. First, what is the goal (getting somewhere at the best speed and safety, being a good driver, etc.), and how important (getting to a wedding or a convenience store for a snack)? Then, what is the cost of obeying the sign (the trip will take longer)? If they disobey, the price could be a ticket or a severe accident. Finally, how does this person view a speed limit culturally and socially (as an unnecessary restriction, or a part of the law, and therefore “good” or “bad”)? This holds in the healthcare workplace as well. Suppose a healthcare worker walks past the same sign daily that reports DO NOT ENTER, and the sign has a huge active magnet picture. They may decide that the sign indicates a danger unlikely to be important at the current time of day and want to cut through to reach the other side of the unit quicker. They have a goal and have decided how important it is and how serious the warning is. They will finally obey the signs in their previous mental calculations and social/ cultural experiences. As an experienced healthcare worker familiar with the building and the various warnings, they may decide to continue through the door despite the warning, which they have determined is irrelevant since MRIs are not performed until 8 am and because they are in a hurry. This example will be investigated further in Case Study #3.