Patients have the right to health care and services that safeguard their dignity and respect their cultural, psychosocial, and spiritual values. These values often affect the patient's treatment needs and preferences. By understanding and respecting patients and their values, healthcare workers can help meet patients' needs for treatment and services and protect their rights. When a patient has dementia or is unconscious, there is a tendency to consider them as objects instead of a person. The patients' privacy and rights must be protected. Patients have the right to participate in decisions about their care and set the course of their treatment. Patients have the right to respectful, non-discriminatory, and compassionate care. Respect means valuing the patients' needs, desires, feelings, and ideas (Sæteren & Nåden, 2021).

Patients must also be treated with common courtesy. For example, a home health aid should knock and wait before entering a patient's room, respond politely to patients, listen to patients, and remain compassionate. According to Malenfant et al. (2022), all patients have the right to fair and equal health care services regardless of the following:

- Race

- Ethnicity

- National origin

- Religion

- Political affiliation

- Level of education

- Place of residence or business

- Age

- Gender

- Marital status

- Personal appearance

- Mental or physical disability

- Sexual orientation

- Genetic information

- Source of payment

CNAs and HHAs can perform personal care services, including hands-on assistance and providing directions to patients during care tasks. CNAs and HHAs are supervised by a registered nurse (RN) and follow a care plan developed by an RN and provider. Personal care services vary based on patient needs, care planning, and state regulations. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025), these services may include:

- Bathing

- Dressing

- Personal hygiene

- Transferring

- Ambulating

- Assistance with eating

- Activities of daily living

- Meal preparation

- Housekeeping chores

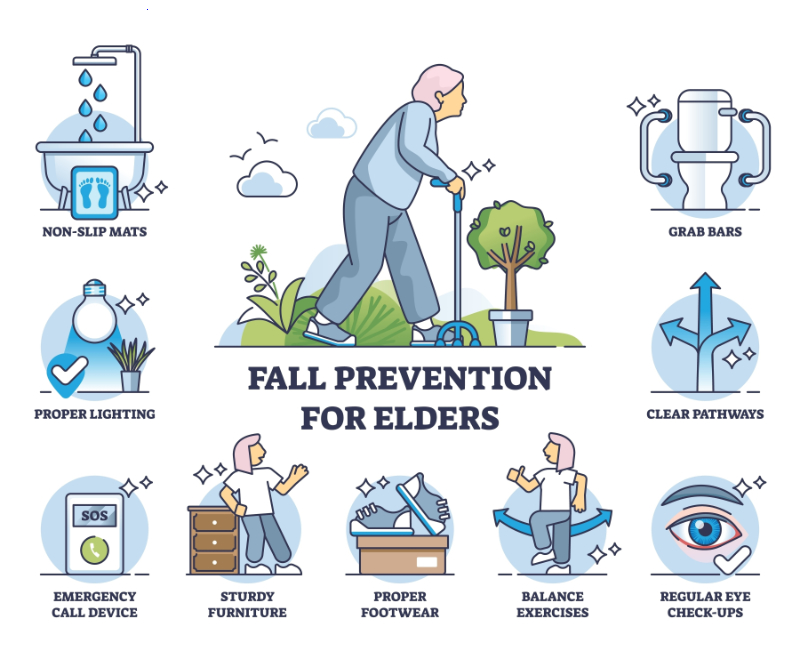

One goal of personal care services is to meet patients' needs while maintaining dignity and independence. One way to achieve this is to have the patients do as much as possible for themselves (Sæteren & Nåden, 2021). The patient may be slow in dressing, but the patient must keep dressing themself to maintain as much function as possible. When patients do not get up to walk, sit up, or use their hands, they can lose function quickly. Patients also benefit from exercise. If specific exercises are on the care plan, a CNA or HHA can coach a patient through a range of motion and strength exercises (Bičíková et al., 2021).

Patients deserve to make choices when they can. Let them choose what to eat, wear, and do other activities if possible. Patients also need mental stimulation unless the care plan says otherwise. Some patients with dementia react badly to stimulation and changes in routine. This may include the introduction to new people, new places, and different eating times (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2025).