The procedures that may need to be performed by the nurse or other trauma team members will vary based on the patient and the mechanism of injuries. As a general rule, members of the trauma team will be expected to know and understand their scope of practice and be able to act accordingly.

The ABCDE algorithm mentioned above can be slightly altered, adding a “C” to the front of the mnemonic for catastrophic bleeding.

Suppose a trauma patient presents with a life-threatening hemorrhage. In that case, the nurse may assist with interventions, such as:

- Initiating a mass transfusion protocol

- Applying a tourniquet

- Applying pressure

- Administering IV fluids

- Dressing wounds

In a compromised airway, the nurse will need to monitor the patient, assess vital signs, administer oxygen, and may even need to administer rescue breaths or use a bag valve mask/Ambu ® bag to provide breaths while awaiting impending intubation.

If a patient presents with an increased breathing difficulty, the nurse may administer medications or supplemental oxygen. If a patient has injuries such as rib fractures, they may also have a pneumothorax, which could require chest tube insertion.

Circulation issues go along with catastrophic bleeding but can occur separately. There could be obvious or no obvious signs of hemorrhage, but the nurse may notice signs during their assessment, such as color or temperature changes, tachycardia, hypotension, etc. The nurse may:

- Perform venipunctures to draw labs

- Apply a pelvic binder in those with pelvic fractures

- Administer fluids and blood products

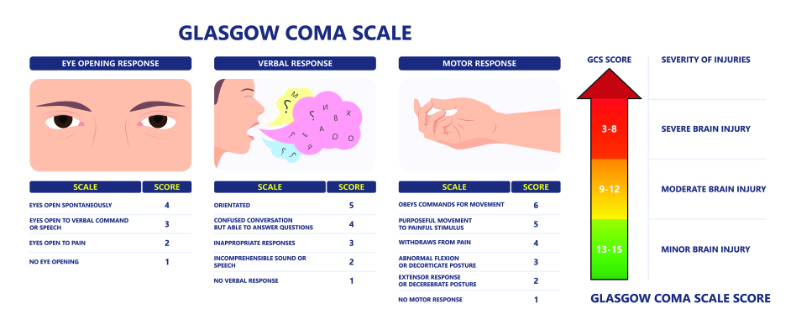

In a disability (or head injury), the nurse is vital in performing an adequate assessment to determine the level of consciousness, the need for further imaging and possible intubation, and additional consults (Lucena-Amaro & Zolfaghari, 2022). Additionally, there is a large quantity of trauma patients who arrive in emergency room settings with hypothermia (Lucena-Amaro & Zolfaghari, 2022). In these circumstances, the nurse may administer warm fluids (or blood products, if indicated), utilize a warming device, such as a Bair Hugger™, use warming blankets, or other interventions to provide optimal outcomes.

Table 1: C-ABCDE Assessment| | Assess For ⇒ Treatment/Management |

| C ⇒ Catastrophic bleeding | Life-threatening hemorrhage ⇒ Apply direct pressure/tourniquet |

| A ⇒ Airway compromise | Patency/position ⇒ Airway protection/jaw thrust to open while maintaining cervical spine |

| B ⇒ Breathing difficulty | Poor respiratory effort ⇒ Provide oxygen supplementation

Pneumothorax ⇒ Chest tube (lung decompression) |

| C ⇒ Circulation (hemorrhagic shock) | Cool skin, tachycardia, bleeding sites ⇒ Apply compression bandage, administer tranexamic acid, transfuse blood |

| D ⇒ Disability (head injury) | Reduced level of consciousness ⇒ Protect airway, transfer ASAP |

| E ⇒ Exposure | Hypoglycemia, hypothermia ⇒ Work to maintain normothermia |

(Mercer, 2018)