Patient Background:

Mr. A is a 45-year-old male who presented to physical therapy with complaints of chronic headaches that had persisted for over five years. He described his headaches as dull and persistent, primarily located in the frontal region with occasional radiation to the temples. These headaches interfere significantly with his daily activities and quality of life. He had previously tried various medications and chiropractic treatments with limited success.

Assessment:

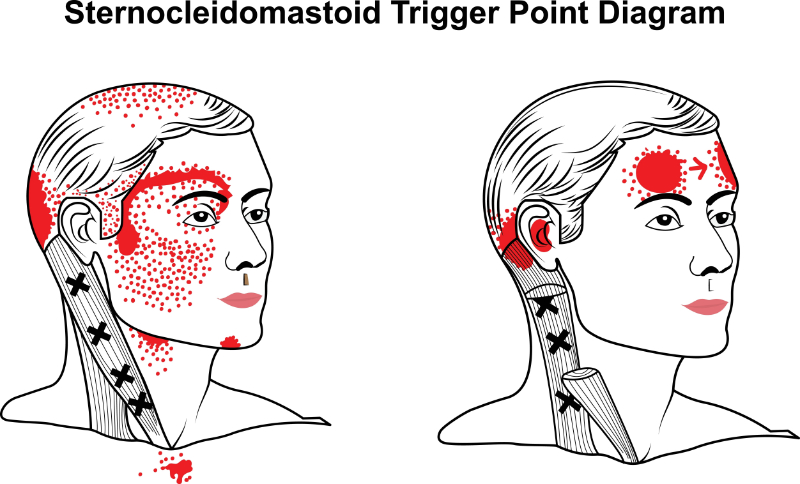

Upon assessment, Mr. A demonstrated a limited range of motion in his cervical spine, particularly in rotation and extension. He had bilateral tenderness in the upper trapezius, suboccipital, and upper cervical paraspinal muscles. Trigger point palpation reproduced his headache symptoms, confirming myofascial involvement in his pain presentation. No neurological deficits were noted during the examination, and Mr.A did not present with any contraindications to dry needling.

Treatment Plan:

Given the findings, a treatment plan incorporating dry needling was discussed and initiated. A consent form was signed and dated. The goals of dry needling for Mr. A included:

- Pain Reduction: Targeting trigger points in the cervical and upper thoracic muscles to alleviate pain and improve function, specifically his upper trapezius, cervical paraspinal, and suboccipital muscles bilaterally.

- Improved Range of Motion: Addressing muscular restrictions contributing to cervical spine mobility impairments.

- Functional Improvement: Enhancing Mr. A's ability to perform daily activities with reduced headache frequency and intensity.

Intervention:

Over six weeks, Mr. A received eight sessions of dry needling, administered twice weekly. Each session targeted specific trigger points identified during the initial assessment. The needles were typically left in place for 10-15 minutes to achieve maximal therapeutic effect with needle rotation at 5 minutes, except for in the upper trapezius. While treating this muscle, an inferior to anterior/superior direction of insertion was utilized into the center of the trigger point until an LTR was achieved. Needle pistoning was performed until LTRs stopped occurring, at which point the needle was removed and disposed of. Mr. A reported minimal discomfort during the procedure and significant relief immediately following each session.

Outcome:

By the fourth session, Mr. A reported a noticeable reduction in headache frequency, intensity, and duration. His range of motion in the cervical spine improved, with decreased tenderness in palpable trigger points. By the conclusion of the treatment period, Mr. A reported being headache-free on most days. He was able to resume activities such as work and exercise without the fear of triggering severe headaches.

Follow-up:

At a one-month follow-up appointment, Mr. A reported continued improvement in headache symptoms. He was advised to perform home exercises to maintain cervical spine mobility and prevent the recurrence of trigger points. A maintenance plan with occasional dry needling sessions was discussed to manage future exacerbations.