No single test exists for Heart Failure diagnosis as it is not one disease. It is a clinical syndrome. Any process that causes functional or structural damage to the cardiac system can start the cardiovascular changes leading to Heart Failure. Diagnosis has historically been based on clinical presentation, client history, and the results of laboratory and imaging studies, including ejection fraction testing.

All of these modalities used as diagnostic tools are good; do not disregard them. It is important to emphasize, especially in those suspected to be in acute Heart Failure, rapidly obtaining a serum natriuretic peptide level (B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP] or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]). These indicators of myocardial damage may not be enough to diagnose Heart Failure on their own. Yet, they do allow a quick rule-out so that another disease process can be diagnosed.

BNP is a hormone secreted from cardiac ventricular myocytes in response to myocardial stretch and stress (Novack & Zevitz, 2021). Its release activates a cascade of pathways, resulting in an overall protective effect on the myocardium (Novack & Zevitz, 2021). A higher BNP level corresponds with greater myocardial tissue damage, allowing an objective measurement that gives a clinical picture of myocardial function when combined with EF.

Due to other conditions, BNP and the other natriuretic peptides used for measurement and tracking damage may be elevated. Therefore, it is important to use ejection fractions as well to ensure it is Heart Failure that you, as a health professional, are tracking (Novack & Zevitz, 2021).

A diagnosis of Heart Failure can be ruled out with (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2021):

- BNP less than 100 ng/L

- NT-proBNP less than 300 ng/L

Should peptide level results be higher than this, it is important to obtain an ejection fraction measurement as quickly as possible for this patient. Remember the new Universal Definition: a high BNP and an EF of less than 40% are diagnostic for Heart Failure.

The following tests have been found helpful in diagnosing Heart Failure.

The current gold standard testing is (Domitru, 2022):

- Ejection Fraction testing by Echocardiogram (or another EF test)

- B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels

- N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels

Procedures that are often diagnostic include (Domitru, 2022; Dallas, 2021):

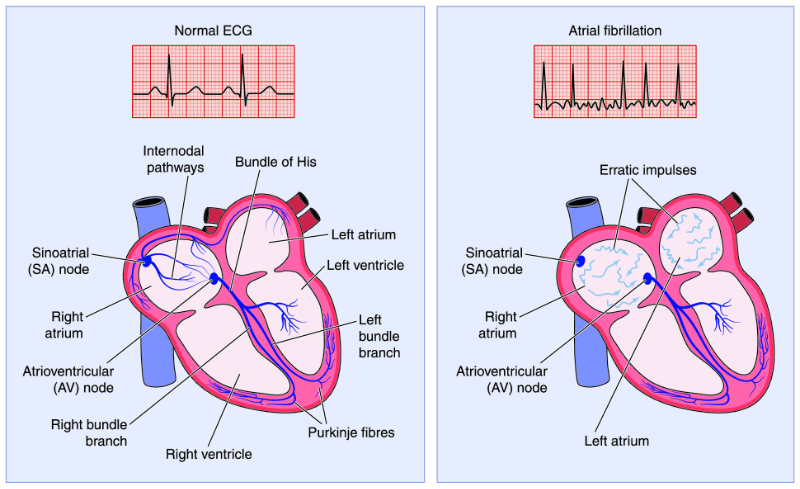

- EKG

- Chest X-Ray

- Stress Test

- Holter Monitor

- Cardiac Catheterization with Angiogram

- Cardiac MRI

Laboratory studies that can also assist in diagnosis (Domitru, 2022):

- Thyroid Function Series (not just a TSH)

- Complete blood cell (CBC) count

- Iron studies

- Urinalysis

- Electrolyte levels

- Renal and liver function studies

- Fasting blood glucose levels

- Lipid profile