*Please note that this case study is not all-inclusive of potential tasks and is meant to serve as a guide.

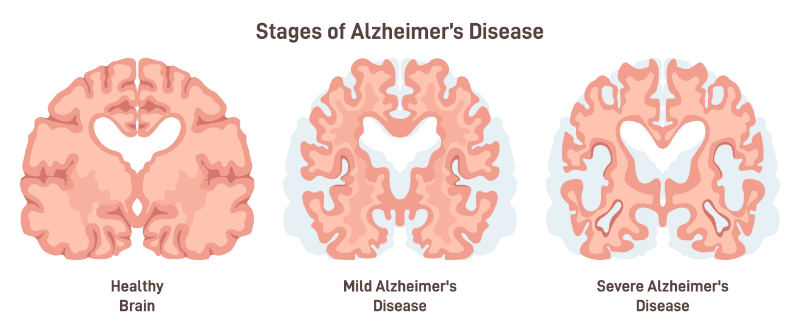

Background: Mrs. Johnson is an 80-year-old patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She has memory loss and confusion and sometimes has a hard time doing daily activities. She has a hard time recognizing familiar faces. She sometimes forgets her daily routine and often needs reminders to finish simple tasks. Her family has counted on the long-term care facility to provide her with the needed support for her needs.

Nursing Assistant’s Role: The nursing assistant, Jackie, plays an important role in providing personal care, watching the health status, and watching out for the comfort of patients like Mrs. Johnson.

In order to make a good routine for Mrs. Johnson, Jackie makes sure that Mrs. Johnson’s activities, meals, and medication times are the same each day. This routine helps decrease her confusion and anxiety, making her feel more safe.

Jackie also makes sure to communicate effectively with Mrs. Johnson by talking clearly and slowly. She uses short and simple sentences. She is patient and gives extra time for Mrs. Johnson to respond. She avoids arguing or correcting Mrs. Johnson if she becomes confused or forgetful.

Since many patients with Alzheimer’s may have impaired judgment, Mrs. Johnson may be at higher risk for accidents. Jackie makes sure that Mrs. Johnson’s room is free of tripping hazards like rugs or cords. She keeps the door closed and locked to decrease any wandering. She also watches Mrs. Johnson closely during activities like bathing or walking to prevent falls.

Sometimes, Mrs. Johnson seems irritated. When this happens, Jackie uses familiar activities, such as listening to music or looking through photo albums, to help Mrs. Johnson feel better. She also talks about Mrs. Johnson’s past.

Sometimes, Mrs. Johnson needs a little help with dressing, mostly to button her shirt properly. To help her remain as independent as possible, Jackie lines up the button holes and then has Mrs. Johnson finish buttoning the buttons.

When Jackie arrived one morning, Mrs. Johnson indicated that she did not feel well. Jackie quickly reported this to her nurse supervisor, who called the family members to ask them to take Mrs. Johnson for a checkup.

Caring for an 80-year-old patient with Alzheimer’s disease takes a lot of planning. By thinking about the patient’s need for routine, safety, communication, emotional support, and independence, Jackie, the nursing assistant, provided good care that helped the patient’s quality of life and dignity.