The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Civil Rights (DHHS OCR): monitors HIPAA complaints, enforces penalties, and provides resources.

Encrypted: Electronic information that has been scrambled so that only someone with the right software code can understand it. Encrypted Apps, such as What’s App and TigerText, can only be read by the sender and receiver. Some medical businesses use these texts, calls, and emails to be secure with PHI. The APP companies can not even read them.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. (HIPAA). This law is called the Insurance Portability and Accountability Act because it was originally (1996) meant to secure health information about patients when used by insurance companies. More laws have been added over time as lawmakers became aware of the increasing need for Privacy and Security in PHI nationally. The word “portability” required the records to be electronic so everyone who needed to use the information could share them (Hester, 2024). All those paper records were faxed everywhere, causing many privacy issues.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule is the specific regulation within the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). It grants patients the right to view, change, or restrict access to their Protected Health Information (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024a).

HIPAA breach or violation: A HIPAA breach is defined as “the unauthorized acquisition, access, use or disclosure of Protected Health Information (PHI) which compromises the security or privacy of such information” (Heath et al., 2021).

Mishandled PHI: When protected information is not properly handled by the people using it, such as putting it into the trash or anywhere anyone can see it, like a computer terminal or on a counter.

The Minimum Necessary Rule. This rule means you only get to see or share the smallest amount of information you or a co-worker need to do your jobs safely.

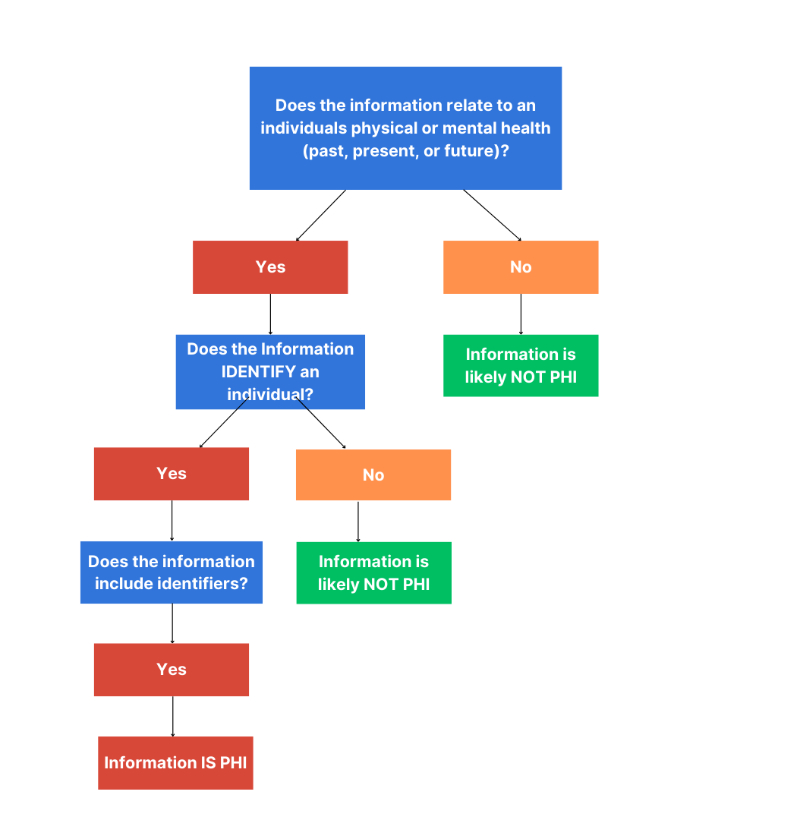

Protected Health Information (PHI) : Is the patient name or “other possible identifier” (photo, rm number, address, social security or driver’s license numbers, family member’s names, neighborhoods, occupations, etc.) linked with the patient’s healthcare info like physical or mental conditions, medications or health history.