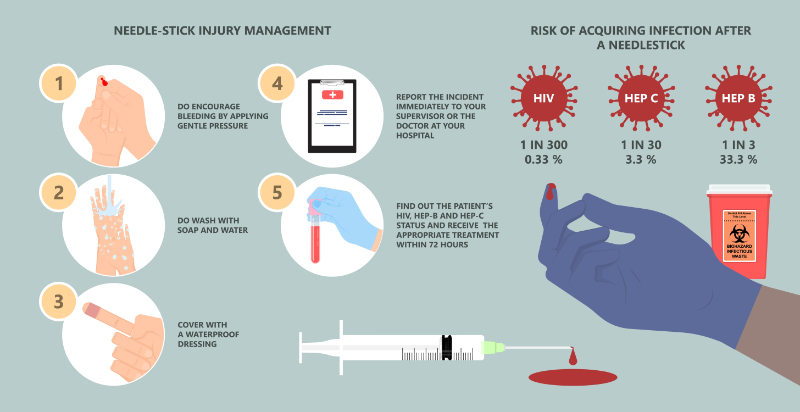

Post-exposure prophylaxis should be given:

- If the source is known to be HIV positive

- While waiting for the results of the source's HIV tests, especially if the source has a high risk of having an HIV infection, and

- If the source's HIV status cannot be determined and if a high-risk needlestick or sharps injury occurred (Zachary, 2023)

Post-exposure prophylaxis with anti-retroviral drugs should be started as soon as possible, preferably within one to two hours post-exposure (National Clinical Consultation Center, 2021; Kuhar et al., 2013; Zachary, 2023). Do not wait for test results unless the results will be available within 1 to 2 hours (National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021). Delaying the use of PEP is likely to diminish its effectiveness (Kuhar et al, 2013). Authoritative sources recommend that PEP should not be given ˃ 72 hours post-exposure (National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021; Zachary, 2023). However, this recommendation is based on drug testing in animals (National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021; Zachary, 2023), and treatment at > 72 hours post-exposure can be considered (National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021; Zachary, 2023). Zachary (2023) wrote, “For most healthcare professionals, we do not initiate PEP if more than 72 hours have elapsed after the initial exposure. However, we do offer PEP after a longer interval to patients with a very high-risk exposure (e.g., sharps injuries from a needle that was in an artery or vein of an HIV-infected source patient)”. For such healthcare professionals, The United States Public Health Service suggests that PEP can be offered up to one week after the exposure.”

It is recommended that clinicians get a consultation if they intend to prescribe PEP > 72 hours post-exposure (National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021). Call the National Clinician Consultation Center at 1-888-448-4911 for advice about this situation.

If the source's rapid HIV test is negative, the employee can discontinue using the PEP (National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021).

Worldwide, recommendations for PEP protocols vary considerably (Maisano et al., 2025). The recommended PEP drug regimens are described below (CDC, 2025; National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021).

CDC PEP Regimen 1: This is the preferred regimen for healthy adults and adolescents

- Emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg (Combination tablet), one tablet once a day, plus

- Raltegravir, 400 mg, one tablet twice a day or

- Dolutegravir, 50 mg, one tablet once a day

CDC PEP Regimen 2: An alternative regimen for healthy adults and adolescents

- Emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg (Combination tablet), one tablet once a day, plus

- Darunavir, 800 mg, one tablet once a day and

- Ritonavir, 100 mg, one tablet once a day

National Clinician Consultation Center PEP Regimen

- Emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg (Combination tablet), one tablet once a day, plus

- Raltegravir 400 mg, one tablet twice a day, or

- Dolutegravir, 50 mg, one tablet once a day

Serum BUN and creatinine, a CBC (complete blood count), and hepatic function tests (LFTs) should be done before starting PEP (CDC, 2025; National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021).

The duration of treatment is 28 days, and these drug regimens are safe and well tolerated(CDC, 2025; National Clinician Consultation Center, 2021). Common adverse effects include diarrhea, fatigue, insomnia, nausea, stomach upset, and vomiting. They are usually self-limiting, and the CDC notes that “... the benefits of HIV prevention outweigh any other risks posed by the medications” (CDC, 2025).

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate can be nephrotoxic. Its use should be avoided in patients with an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2(Zachary, 2023), and an alternative should be used.

Abacavir sulfate should not be used in any PEP regimen (CDC, 2025). It has been linked to potentially fatal hypersensitivity reactions. These are more likely to occur in people with the HLA-B*57:01 allele (Mounzer et al., 2019), and because PEP must be started as soon as possible, there is no time for genetic testing (CDC, 2025).