Mr. John Smith, a 68-year-old male, is found by his wife slumped on the living room couch. His wife observes that the right side of his face is drooping, and when he tries to speak, his words are slurred and difficult to understand. She also notices that he is unable to lift his right arm when asked. His wife states that Mr. Smith was "acting completely normal" approximately 30 minutes ago, before she went to check the mail. Recognizing these sudden changes, she immediately calls 911. Mr. Smith has a known medical history of uncontrolled hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, for which he takes daily medications, though he sometimes forgets to take them regularly. He also has a history of AFib, which is managed with a blood thinner.

Assessment:

Upon arrival, EMS personnel conduct a rapid initial assessment.

EMS quickly applies the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale. They observe a clear facial droop on the right side, right arm drift when asked to raise both arms, and abnormal speech (dysarthria). Based on these findings, a stroke is highly suspected.

Mr. Smith's wife confirms that he was last seen without symptoms 30 minutes ago. This "last known well" time is immediately documented and communicated to the hospital.

His blood pressure is recorded as 190/110 mmHg, and his heart rate is irregularly irregular at 110 beats per minute.

Pre-Notification:

EMS immediately pre-notifies the nearest designated Comprehensive Stroke Center, providing a brief report on Mr. Smith's symptoms, "last known well" time, and estimated time of arrival.

Upon arrival at the emergency department, the stroke team is activated and ready.

Mr. Smith is immediately moved to a dedicated stroke bay.

A neurologist performs a comprehensive neurological examination, including the NIHSS. His initial NIHSS score is 14, indicating significant neurological deficits affecting motor function, speech, and facial symmetry.

Imaging:

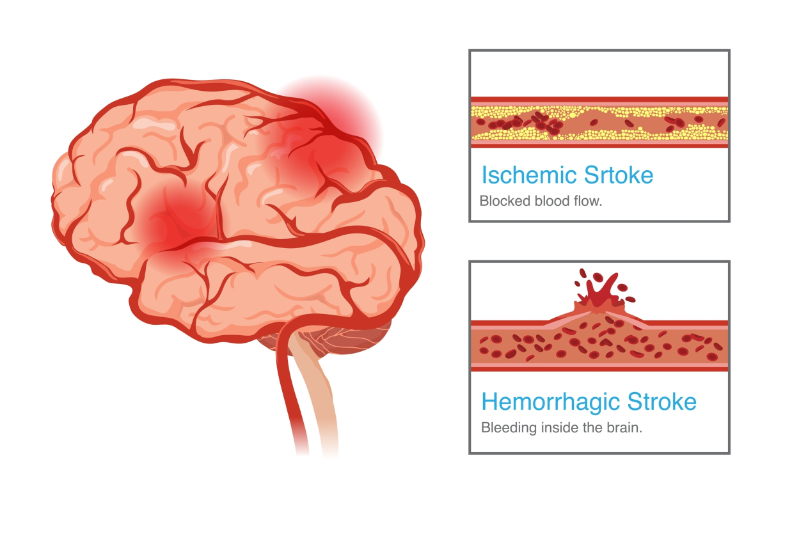

A non-contrast CT scan of the brain is performed within ten minutes of arrival. The CT scan reveals no evidence of intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding). This finding confirms the likely diagnosis of an ischemic stroke. A CT angiography (CTA) is also performed to identify any large vessel occlusions that might be amenable to mechanical thrombectomy. The CTA confirms a large clot in the middle cerebral artery.

Blood tests are drawn, including blood glucose, coagulation studies, and a complete blood count. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is performed, confirming Afib.

Intervention:

Based on the rapid assessment and diagnostic findings, immediate interventions are initiated to restore blood flow to Mr. Smith's brain.

Given that Mr. Smith's "last known well" time is within the 4.5-hour window for thrombolytic therapy, and there is no evidence of hemorrhage on the CT scan, intravenous alteplase (tPA) is administered. The nursing staff closely monitors his neurological status, vital signs (especially blood pressure), and watches for any signs of bleeding.

Endovascular Intervention (Mechanical Thrombectomy): Because the CTA identified a large vessel occlusion and Mr. Smith meets the criteria, he is immediately prepared for a mechanical thrombectomy. This procedure is performed in the interventional radiology suite, where a catheter is guided to the clot in his middle cerebral artery, and the clot is successfully removed.

Medical Management:

His blood pressure is carefully managed with intravenous medications to keep it within a safe range (typically below 185/110 mmHg before tPA, and then lower after tPA) to prevent further brain injury or hemorrhagic transformation.

His blood glucose levels are monitored and managed to prevent hyperglycemia, which can worsen stroke outcomes. His temperature is monitored, and if a fever develops, it is promptly treated.

Throughout this acute phase, nursing staff perform frequent neurological assessments (every 15-30 minutes), ensure patient safety by implementing fall and aspiration precautions, and maintain strict fluid and electrolyte balance.

Discussion of Outcomes:

The rapid and coordinated acute stroke response significantly impacted Mr. Smith's outcome.

Within hours of the mechanical thrombectomy, Mr. Smith's neurological deficits began to improve. His facial droop became less pronounced, his speech became clearer, and he regained significant strength in his right arm and leg. His NIHSS score decreased to 4 within 24 hours, indicating a mild residual deficit.

Due to vigilant nursing care, Mr. Smith did not develop any pressure injuries. His blood pressure and blood glucose remained well-controlled, minimizing secondary brain injury. A bedside swallow screen was performed, and he was placed on aspiration precautions until a formal swallow evaluation by a speech-language pathologist confirmed he could safely swallow thin liquids and a regular diet.

Within 24 hours of his stroke, physical and occupational therapists began working with him at his bedside, focusing on early mobilization and exercises to prevent deconditioning and promote recovery.

After a few days in the acute care setting, Mr. Smith was medically stable enough to be discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. The interdisciplinary team (including social work) collaborated with him and his family to ensure a smooth transition, setting realistic goals for his continued recovery. His family was educated on his medications and the importance of adherence.

Mr. Smith's case highlights how timely intervention, adherence to stroke protocols, and comprehensive interdisciplinary care can lead to significant recovery and improved long-term outcomes for stroke patients. His continued rehabilitation and diligent management of his risk factors will be key to preventing future strokes.