Patient Description

Mr. Joseph H., a 64-year-old retired postal worker, presented to New Dawn Primary Care Clinic for his scheduled appointment with Nurse Practitioner Amanda. He reports a 3-day history of localized neuropathic pain and sensory disturbances localized to the left mid-back. He described the discomfort as sharp, burning, and shock-like sensations, which he rated as 7 out of 10 in severity. The pain had been persistent, interfering with his sleep and daily routines. Within 24 hours of the initial symptoms, he developed clusters of painful, fluid-filled blisters in the same region. Mr. H. denied fever, headache, or systemic symptoms. He has a medical history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, managed with lisinopril and metformin. Notably, he had never received the shingles (herpes zoster) vaccine, despite meeting CDC age-based eligibility recommendations. He expressed regret about this, stating he was unaware of the vaccine's availability and importance.

The patient lives alone in a private apartment and reports no recent illness, known exposures, or travel. He maintains regular follow-up with his primary care provider for chronic disease management, but reported missing his last wellness visit. His diabetes has been moderately controlled, with a recent HbA1c of 7.5%. He denied any known immunosuppressive conditions or medications. The nurse practitioner recognized that Mr. H.'s age, diabetic status, and lack of vaccination placed him at increased risk for reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus (VZV), leading to shingles. The timing, pain characteristics, and sudden vesicular eruption raised a strong clinical suspicion for herpes zoster.

Clinical Presentation

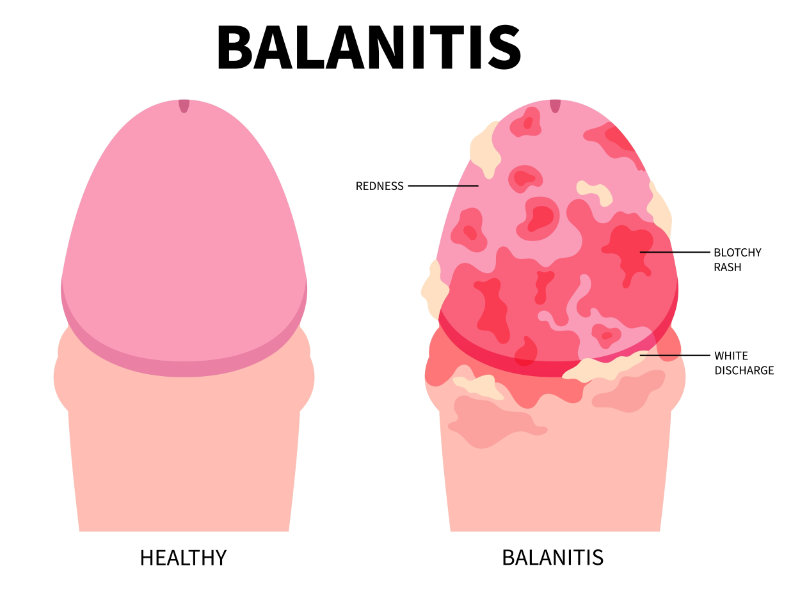

On physical examination, the evaluating nurse practitioner noted a unilateral eruption of grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, following the left T8 dermatome in a linear, dermatomal pattern. The lesions did not cross the midline, which is characteristic of herpes zoster. The vesicles were tense and clear, some beginning to crust at the margins. The surrounding skin showed signs of mild edema and tenderness to light palpation. No signs of systemic involvement, dissemination, or ocular complications were present. Lymphadenopathy was not appreciated, and the patient remained afebrile. Cranial nerves were intact, and the neurological exam was unremarkable beyond the localized hyperesthesia in the affected dermatome.

The nurse practitioner made a clinical diagnosis of herpes zoster based on the patient's age, symptomatology, and physical findings. Given the classic presentation and absence of red-flag features, no further laboratory or imaging studies were indicated. She discussed the natural course of shingles and emphasized the need for early antiviral therapy to reduce the duration and severity of symptoms and to mitigate the risk of postherpetic neuralgia, a common complication in older adults.

Nurse Practitioner Intervention and Management

The nurse practitioner prescribed valacyclovir 1,000 milligrams (mg) by mouth three times daily for seven days. This antiviral therapy was selected based on current clinical guidelines, which recommend initiating treatment early to reduce the severity and duration of symptoms. The goal was also to decrease the risk of complications such as postherpetic neuralgia, especially given the patient's age and history of type 2 diabetes. Acetaminophen was recommended for pain relief, and the patient was advised to take it regularly during the acute phase.

Patient education focused on safe practices to limit the spread of the virus and prevent secondary skin infections. Joseph was instructed to gently clean and cover the rash, wear loose clothing, and avoid touching or scratching the affected area. He was also advised to avoid contact with individuals at higher risk for severe varicella-zoster virus infection, including pregnant women, infants, and people with weakened immune systems. The nurse practitioner explained the warning signs of secondary infection, such as spreading redness, swelling, or discharge, and encouraged prompt follow-up if symptoms worsened or did not improve.

Preventive care was also addressed. The nurse practitioner provided information on the recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix), including its role in reducing the risk of future outbreaks and related complications. Although the vaccine cannot be given during active infection, the patient was encouraged to receive it after his skin lesions fully resolved. The discussion also included tips on supporting immune health, such as good blood sugar control, balanced nutrition, adequate sleep, and stress reduction.

Outcome

At his follow-up visit one week later, Joseph reported that the pain had decreased significantly. He described it as a dull ache, now rated 3 out of 10, compared to the initial sharp and burning discomfort. Most of the blisters had crusted, and there was no evidence of new lesions or signs of bacterial infection. His sleep had improved, and he expressed a greater sense of comfort and independence.

Joseph shared that he had followed the home care instructions carefully and appreciated the clear, supportive communication he received during his first visit. He stated that the education helped him understand the condition and feel more confident managing it. He expressed interest in getting the shingles vaccine once the rash healed and was provided with follow-up guidance and educational materials. The nurse practitioner reinforced the importance of continuing self-care and monitoring for any lingering pain that might indicate nerve involvement. Overall, the patient's recovery was progressing well, with no complications reported at this time.

Strengths of the Approach

- Rapid recognition and diagnosis of a classic dermatomal rash.

- Timely initiation of evidence-based antiviral therapy.

- Proactive education on disease transmission, pain management, and preventive vaccination.

- Patient-centered communication tailored to age and chronic condition management.

Opportunities for Growth

- Consideration of adjunct neuropathic pain options (e.g., gabapentin) for potential postherpetic neuralgia.

- More thorough assessment of psychosocial impact and sleep disturbances related to pain.

Reflection Questions

What is the role of the NP in reducing complications associated with shingles?

- Nurse practitioners play a key role in early detection, prompt antiviral treatment, and preventive counseling to minimize risks such as postherpetic neuralgia.

Why is patient education essential in managing herpes zoster?

- Understanding transmission, skin care, and vaccination empowers patients to reduce spread, improve outcomes, and make informed decisions about future prevention.