Edi is always on the go. But then again, it is all she has ever known! Growing up in a military family meant moving all the time to bases all around the world. She liked it – the cultural immersion from the experiences gave her a sense of appreciation for diversity and all the different kinds of people and traditions. Her only regret is that it made it hard for her to keep in touch with her extended family. She remembered stories about some of them from when she was young, and they would write to each other as often as possible, but she always looked forward to those fleeting times when they could all get together at a reunion! The discipline and structure that military life fostered were probably a big reason that Edi fell in love with physics. The math, the laws, it just made sense! Her interests grew naturally in the natural sciences, and she worked on many federally funded projects for NASA.

Today, Edi is stopping by to see her PCP, Dr. Werner. An exceedingly serious man, Dr. Werner is a man of few words. Sharp as a tack, he has an exceptionally staid personality. “Edi, I’ve been reviewing your family medical history, and I have some concerns. Your mother’s side of the family has a troubling pattern of cancer diagnoses.”

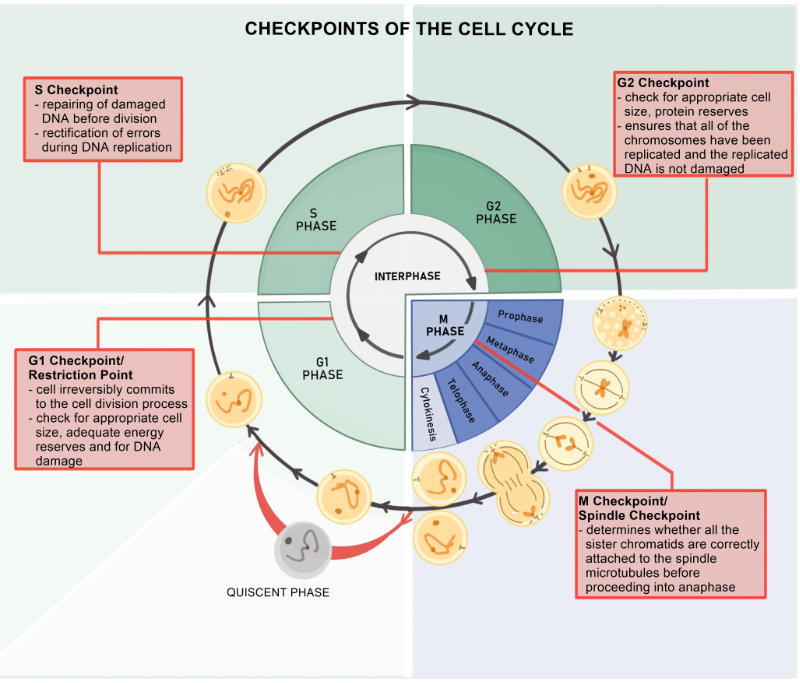

Edi had heard the stories. Her maternal grandfather had passed away at the age of 54 from CRC. Since it had been diagnosed at age 49, he had undergone genetic testing and was found to carry a mutation in PMS2, effectively inactivating the gene. Without the resulting protein, Dr. Werner explained, her grandfather’s cells could not correct stochastic mistakes in DNA replication. This was a process known as DNA mismatch repair (MMR). These mutations added up over time and ultimately struck her grandfather’s KRAS gene, a proto-oncogene that drives cellular growth and differentiation. “That must have caused his cancer!” Edi declared. “I remember my mother telling me they did something called next-generation sequencing that identified the mutation. “Next-generation sequencing,” Dr. Werner confirmed, “is a powerful tool that modern clinicians can use to identify mutations that may be targetable for treatment. It’s personalized medicine.”

“I’d like to recommend we get you genetic testing,” Dr. Werner said. “I noticed your maternal uncle passed away from urothelial cell carcinoma at age 61, and his son, your cousin, passed away very young from a small bowel cancer. By Amsterdam II criteria, we can clinically diagnose you with LS once we rule out familial adenomatous polyposis based on these other clinical factors.”

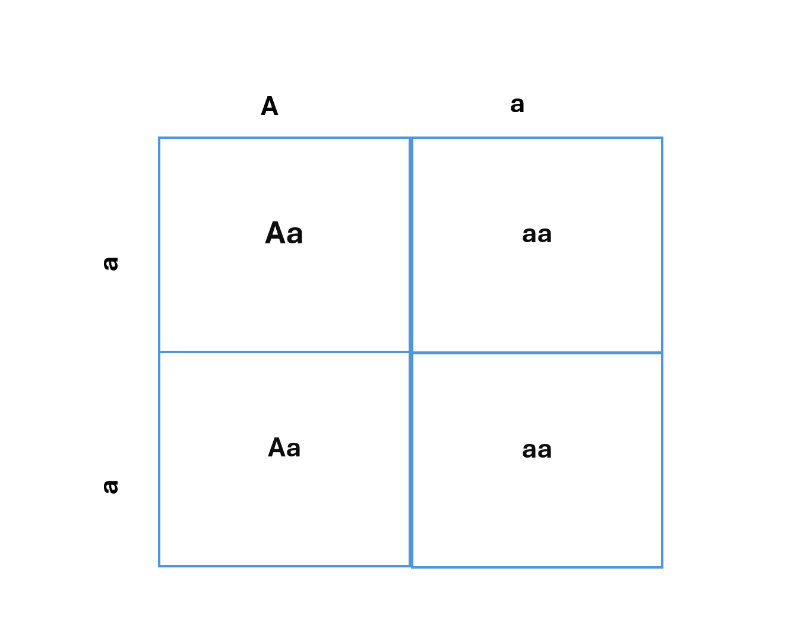

“I don’t think that’s necessary,” Edi said. “I appreciate your concern, but it’s obvious to me that my uncle inherited the allele from my grandfather, but my mom is in her 60s now and has never had a cancer diagnosis. Even though she hasn’t been tested, it’s clear to me that we didn’t inherit the allele.”

- Do you agree with Edi? Is there any value in her undergoing genetic testing, given that her mother, now in her 60s, has not had a cancer diagnosis? Why or why not?

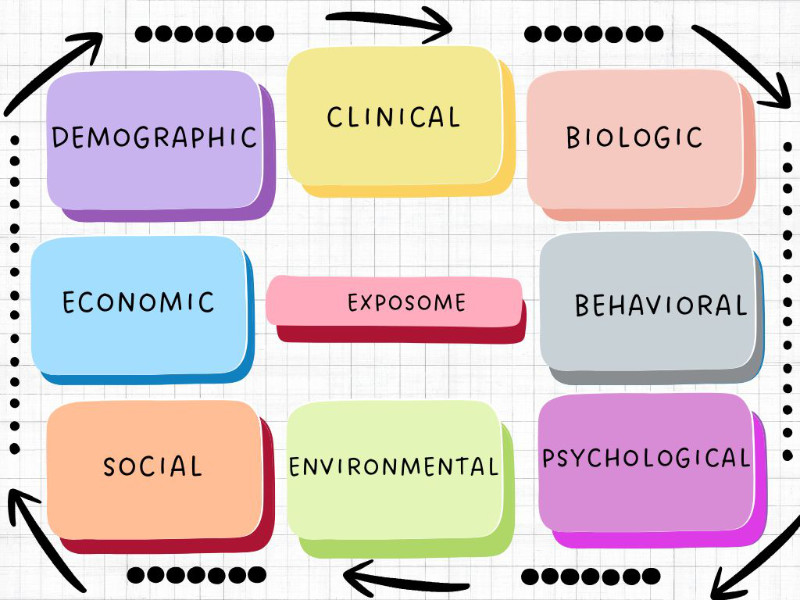

- A: No, I would disagree with Edi. LS is known to exhibit incomplete penetrance, which means the allele is inherited, but sometimes cancer never manifests. It is important to clarify that carrying the allele does not guarantee a cancer diagnosis; rather, it informs lifetime risk, which can give insight into preventive behaviors, including regular screening, avoiding certain exposures associated with CRC risk, and active surveillance for symptoms of CRC, including cramping, bleeding, and bowel changes. Furthermore, all of the cancers in Edi’s pedigree are LS-related cancers.

“Wow, I never knew that!” Edi exclaimed. “Yes,” Dr. Werner explained, “Due to incomplete penetrance, it’s possible that your mother carries the allele and just has been lucky to never develop a cancer.”

“Let’s get me tested!” Edi says.

Edi’s blood sample confirms a germline mutation in PMS2 by immunohistochemistry. Dr. Werner can work with her to organize a screening plan that works around her busy life, ensuring they have the best chance of catching any Lynch-related cancers early. “I have another question,” Edi says. “When my grandfather had next-generation sequencing testing done, the doctors were able to give him some prognostic information, but at the time, there weren’t any targeted therapies available to him. Is that still the case?”

Dr. Werner opens the electronic health record. “It’s interesting that you mention that because in 2021, the FDA approved sotorasib for the specific KRAS mutation that your grandfather had – KRASG12C. The notation means that at amino acid position twelve, the mutation has led to a cysteine residue where there is normally a glycine. That change in amino acid makes the protein constitutively active, or always “on” (Heriyanto et al., 2024). Sotorasib received accelerated approval based on a study called CodeBreaK 100 because it is a small molecule that can bind very specifically to the KRAS protein to keep it permanently “off”. The company followed that trial up with a study called CodeBreak 200, which sought to move sotorasib to the first line in KRASG12C mutated cancers like non-small cell lung cancer and CRC.”

More data from the study can be found here. If you were a clinician counseling a patient on their treatment options for a metastatic CRC, which was known to be KRASG12C positive, what are some considerations that you would ensure to include in the conversation with your patients (de Langen et al., 2023)?

Research has shown that there is a modest progression-free survival benefit in the sotorasib group as compared to the docetaxel group. Sotorasib also appears to have a favorable toxicity profile as compared to docetaxel (33% Grade 3+ adverse events for sotorasib, 40% Grade 3+ adverse events for docetaxel). As a taxane, docetaxel comes with many of the “classic” chemotherapy side effects such as hair loss, nausea and vomiting, and peripheral neuropathy. All of these can be quite distressing to patients. Sotorasib side effects tend to be milder, manifesting in ways like liver function test elevations. Sotorasib also benefits from oral administration, eschewing the need to travel to an infusion center to receive intravenous chemotherapy. Despite these advantages, the cost difference is significant, with sotorasib costing nearly $15,000 per cycle (21 days) and docetaxel costing only $77 per cycle (Jiang et al., 2023).

Ethically, these multifaceted considerations need to be thoroughly addressed with patients. For example, if you have screened a patient for food insecurity and they admit to having trouble affording groceries, it would be necessary to have a frank conversation with them about the cost of sotorasib, not to deter them, but to make sure they have a crystal clear understanding of what they can expect when they make their decision.

In terms of trauma-informed care, understanding whether your patient has gone through chemotherapy before or has been a caregiver for another person who has undergone chemotherapy may provide important insights into whether or not receiving additional chemo could be a trigger for them, which may indicate that the targeted therapy is a better choice from that perspective.

In terms of mechanism of action, medication adherence is imperative for the patient taking sotorasib because the cancer will continue to grow if the patient stops taking the pill. Therefore, thorough patient education regarding adherence is necessary.

If testing could be done to assess pharmacogenomics, perhaps the patient could be found to be a slower-than-average metabolizer of this drug, which means they could be prescribed less to achieve the therapeutic benefit and possibly lower the cost to the patient.