Famous Nurses: Clara Barton, Angel of the Battlefield

Clara Barton was no stranger to the dangers of war: while serving as a nurse during the Civil War, a bullet skimmed her sleeve and killed the soldier she was caring for. “A ball had passed between my body and the right arm which supported him, cutting through the sleeve and passing through his chest from shoulder to shoulder,” she recalled. “There was no more to be done for him and I left him to his rest. I have never mended that hole in my sleeve.”

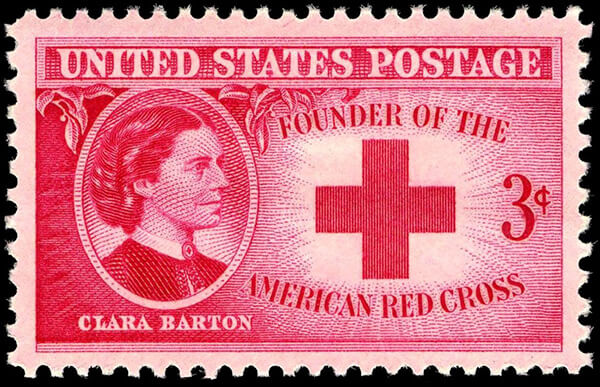

Clara’s legacy is evident in many aspects of American history, including serving as a nurse during the Civil War, contributing to the women’s suffrage movement, and helping to establish the American Red Cross.

In order to clearly see the breadth of Clara Barton’s impact we must look at her whole life, including her time as a youth and as a teacher, her experiences during the Civil War, and her role in the creation of the American Red Cross.

As a Youth and On the Job

Many children have ideas of what they want to be when they grow up. Between caring for her brother David and growing up with a father who was a war veteran, Clara Barton’s childhood set her up for a nursing legacy—although that wasn’t her original plan. Explore her upbringing and early career as a teacher before diving into her life as a nurse.

Early Life

Clara’s life began on December 25, 1821, in Oxford, Massachusetts. Her father was a successful farmer and active in the community. Clara grew up hearing her father’s war stories as he recounted his experiences in the Indian wars. She gained most of her early education learning from him and her four older siblings.

When Clara was 11, her brother David was injured in a barn-raising accident. Clara’s experience as a nurse began with this very situation: she nursed her brother back to health for two years following the accident.

Early Career

Clara was known for her shyness—so much so, in fact, that her mother took her to see a phrenologist, who suggested she pursue a career in teaching “to overcome her shyness.” With her family’s encouragement, Clara began teaching in 1838 at the age of 18, standing out in a time period when most teachers were men. She built a very positive reputation as a teacher, and she never used physical punishment—a common practice at the time—to keep her students in line.

“After seeing a group of boys doing nothing on a sidewalk, Clara opened a school where all people, rich or poor, could attend,” says TruthAboutNursing.org. The school was built with workers’ children in mind, and it stands as an example of Clara’s desire to serve and care for people. The National Women’s History Museum states that Clara later moved to Bordentown, New Jersey and “established the first free school there in 1852. She resigned when she discovered that the school had hired a man at twice her salary, saying she would never work for less than a man.” Thus began her efforts as an advocate for women’s rights.

Following this experience, Clara moved to Washington, DC, to work for the US government patent office, where she became the office’s first female clerk. In 1861, the Baltimore Riot occurred, in which Southern-supporting mobbers killed and injured both soldiers and civilians. Clara helped care for those who were injured and gathered basic essentials for the needy soldiers. “Clara wrote friends in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey urging them to help, soon building a volunteer supply network that would last the entirety of the war.”

During the Civil War

Clara’s decision to quit her job in 1861 and serve injured soldiers began a journey of medical care that she would pursue for the rest of her life. Her nickname, “Angel of the Battlefield,” was fitting as she treated the wounded, delivered supplies, and offered leadership skills that she naturally acquired throughout her life. Between her normal duties, dedication to finding missing men, leading medical teams into dangerous territory, and ultimately establishing the Red Cross, Clara played a crucial role in the Civil War.

Clara’s Duties

To put into perspective how remarkable Clara’s contributions were to the war, it’s important to note that she never received formal medical training. Despite this, she served as a head nurse and entered dangerous areas of war to reach soldiers who needed immediate attention. “She joined Frances Gage in helping to prepare slaves for the lives in freedom,” states the National Women’s History Museum. Wherever there was a need, she did what was necessary to help.

Clara traveled from battle to battle, delivering supplies and treating the many wounds soldiers endured. She helped soldiers from both sides of the conflict. It’s hard to know when Clara slept; throughout her time helping soldiers, she set up a soup kitchen, field hospitals, and, in her personal journal, recorded the names of soldiers who died.

Clara’s experiences were far from ordinary. “At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862, she saw a fragment from an exploding shell sever a soldier’s artery and applied a tourniquet that saved his life,” recounts historynet.com. “When a shell struck the door of the room she was in, she continued what she was doing as though nothing happened.”

One of Clara’s responsibilities became leading diet and nursing at a hospital. The hospital was “dubbed a ‘flying hospital’ because of its frequent moves to be close enough to battle to help the wounded but not so close as to be overrun.”

Battlefield Medical Care

Clara didn’t settle for letting the wounded be brought to her; she petitioned to be allowed to care for soldiers on the very battlefields and hospitals where the action was happening. One soldier recalled, “I thought that night if heaven ever sent out a[n] . . . angel, she must be one—her assistance was so timely.” Clara would make sure supplies were always on their way when a battle was in movement. Her humility was admirable and evident when she would say things like, “I always tried . . . to succor the wounded until medical aid and supplies could come up—I could run the risk; it made no difference to anyone if I were shot or taken prisoner.” On the contrary, the Civil War and other events following the war would have been very different without Clara.

Clara’s Boys

When Clara began helping soldiers in Maryland, she found out that she knew many of the boys from this unit, calling them “her boys.” She helped equip these men and their fellow soldiers with basic essentials they desperately needed, representing the US Sanitary Commission. The Red Cross says she even “offered personal support to the men in hopes of keeping their spirits up: she read to them, wrote letters for them, listened to their personal problems, and prayed with them.”

Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army

In 1865, President Abraham Lincoln asked Clara to find missing soldiers who had been separated from their comrades. According to the Smithsonian Institution, “By the time the office closed in 1867, she and her staff had responded to more than 63,000 letters from grieving parents, family, and friends whose sons, brothers, and neighbors were missing. Their work identified the fate of more than 22,000 men.” Her process was to take the suggested names and distribute them to newspapers, post offices, and other entities that could get the word out and ask for information about these missing soldiers. Later on, she was asked to help identify and mark about 13,000 graves.

Journey to the Red Cross

During her service, Clara was exposed to the International Committee of the Red Cross, where she got the inspiration to bring the Red Cross to America. Over time, after trying to ease government fears of the risks of joining international organizations, the United States government approved the creation of the American Red Cross. In order to promote the formation of the American branch of the Red Cross, Clara wrote and distributed pamphlets, held lectures, and met with President Hayes.

Creating the American Red Cross

“Barton read A Memory of Solferino, a book written by Henry Dunant, founder of the global Red Cross network,” reports The American National Red Cross. “Dunant called for international agreements to protect the sick and wounded during wartime without respect to nationality and for the formation of national societies to give aid voluntarily on a neutral basis.” In other words, forming an American branch of the Red Cross was directly in line with what Clara stood for.

Once the United States government ratified the Geneva Conventions, the Red Cross was established in America, and Clara was declared president of the organization in the United States. This opportunity was a crowning jewel on the selfless sacrifice she offered throughout her life. Much was accomplished during Clara’s time as president, and the many duties and accomplishments by the Red Cross have helped countless people and communities during times of need and disaster.

Duties of the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross, along with its fellow international branches, provides services in almost every capacity required to deliver relief and care to those in need. Clara paved the way for establishing the standard of care when the Red Cross was brought to America. During her time and today, these are some of the services provided by The American Red Cross:

- Distribute supplies

- Make new clothes

- Give physical and mental health services

- Provide shelter

- Enable emergency communications

- Train and support wounded veterans

- Run blood drives

- Hold safety training programs

- Teach the rules of war

- Provide financial assistance

Historical Contributions of the American Red Cross

Since its inception, the American Red Cross has delivered aid to people and communities all over the world. Here are some of the early contributions Clara was involved in:

- 1881: Delivered aid and clothing to Michigan forest fire victims

- 1884: Delivered supplies to flood victims Ohio and Mississippi

- 1889: Helped those affected by a dam break that killed over 2,000 people

- 1892: Provided food during a Russian famine

- 1893: Helped African-American citizens strengthen their agricultural endeavors

- 1896: Delivered help to those affected by violence in a Turkish–Armenian conflict

- 1990: Gave $120K and supplies to victims of Galveston, Texas, hurricane

End of Life

Disagreements in how Clara ran the American Red Cross, combined with health problems and age, led to Barton’s resignation in 1904. Barton continued to use her talents and compassion in whatever form was needed. The Red Cross states that she was involved in “education, prison reform, women’s suffrage, civil rights, and even spiritualism. Her force and independent spirit created opponents, but her charm attracted many loyal followers. She was struck by a period of severe depression throughout her life but always seemed to revive quickly when a major calamity called for her services. . . . She was said to be somewhat vain about her appearance, particularly her hair, although she did not consider herself a pretty woman. She liked dashes of bold color on her clothing, especially red.”

Clara died on April 12, 1912, at the age of 90. Just seven years before her death, she created the National First Aid Association of America, an organization which provided insight on first aid instruction and emergency preparedness. She was awarded multiple international recognitions, including the Silver Cross of Imperial Russia and the German Iron Cross.

In 1975, Clara’s home in Maryland was declared a National Historic Site—the first time a woman’s place of living received this recognition.